— by Chryseis

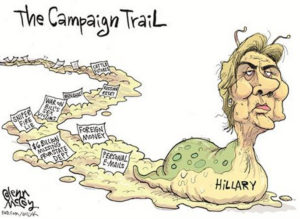

I was amused to read Michelle Goldberg’s article “Will We Ever Have a Woman As President?” in the May 31, 2017 issue of Slate (http://bit.ly/2sgc2ZF). The overall theme that runs through her piece is that Hillary Clinton’s defeat for the presidency of the United States was a defeat for all women, which makes the chances of a woman becoming President more remote. Her piece is pure “Chicken Little” because Hillary Clinton alone is responsible for her loss.

It is a complete myth for Michelle Goldberg to argue that Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 presidential elections primarily because she was a woman. To be sure, there must be some men and even some women who disqualified Hillary Clinton only because she was a woman. In 21st Century America, these people are an anomaly and their vote counts as much as the Pennsylvania Amish or Quakers.

The truth is that Hillary Clinton alone is responsible for her own defeat in 2016. She was not a relatively fresh face to the political scene like Barack Obama was in 2008. She has been a fixture in national politics since she arrived in Washington, D.C. with her husband President William Jefferson Clinton in 1992. Her candidacy was based on Senate back-bencher seniority, “It’s Hillary Clinton’s turn now”. This contributed to the same staleness as the campaigns of 1996 Republican candidate Bob Dole, 2004 Democratic candidate John Kerry, and 2008 Republican candidate John McCain. Had she chosen to run in 2004, she could have possibly beaten John Kerry, and then she could have been that fresh-faced candidate. She played it safe in 2004 and her train left the station.

There was no mystery to Hillary Clinton. She did not electrify the voters. She was a known quantity. She had a long paper trail that every voter knew exactly who she was and what little she stood for. In 2016, every liberal who loved her over the past 25 years voted for her. Every voter who disliked her over the past 25 years did not. Both her supporters and her detractors knew very well that her political positions were a revolving door and that she would say anything and stand for anything if her army of pollsters told her that the position would gain her some small advantage with some constituency.

Hillary Clinton’s calculating nature was made even more obvious by her chameleon-like tendency to speak in different accents to different constituencies. Among African-American voters, she adopted their speech patterns. When she spoke to southerners, out came the southern accent. In the Northeast, she became the highly educated Wellesley College and Yale Law School graduate. When she visited the Midwest, she was the prodigal Midwesterner daughter. When wining and dining donors in Silicon Valley, California, she spoke a different language than to her voters in Brooklyn and Long Island. She probably had as many accents up her sleeve as Mel Blanc, the voice behind all the old school Warner Brothers cartoons.

Michelle Goldberg’s piece claims that Hillary Clinton’s defeat was due in large part to misogynist men who felt threatened by smart, assertive, policy wonk female candidates like Hillary Clinton. She thinks that Hillary Clinton was unfairly held up to the sexist double standard of lack of likability and lack of toughness. Sexism and misogyny are the excuse. Unlikability and lack of authenticity are not the problem with all female candidates, just with Hillary Clinton and female candidates like her. The problem was Hillary Clinton. She had a track record of 25 years of failed government solutions to problems. She truly was a limousine liberal. Because she had not driven a car in more than three decades and was chauffeured everywhere in a government limousine, she never experienced dealing with the Department of Motor Vehicles or with government workers as did ordinary Americans. She knew nothing about the lives of the ordinary women that she claimed to speak and legislate for.

It is fair to say that both men and women dislike in equal measures women like Hillary Clinton, who is the grown up version of the bossy Lucy van Pelt from the “Peanuts” comics strip. Hillary van Pelt is the brassy and controlling busybody character that every American man and woman hates and must endure in high school. She entrenches herself in student government in high school and in college. She loves to order lesser people around because she always knows what is best for them. Armed with a sharp tongue and a degree from a fancy law school, she knows that the solution to every problem on earth is another big government program run by herself, administered by entitled bureaucrats, and lavishly funded by taxpayers.

Hillary Clinton was not the victim of sexism and a “vast right-wing conspiracy” against liberal women. She is really an opportunist, who uses the accusations as a shield for herself. She ran the Clinton Foundation like a criminal syndicate to stuff her pockets while collecting a government salary as the Secretary of State. She collected from lobbyists hundreds of millions of dollars in shady donations for the Clinton Foundation, trading them government favors to oppressive foreign governments, Silicon Valley, and Wall Street hedge funds. She set up a private e-mail server in her basement so that her Clinton Foundation’s dealings would not be through a government e-mail account that could be the target of Freedom of Information requests. She sent e-mails that were classified “top secret” through this server, including forwarding them for printing to her foreign maid who did not have top secret government clearance. She destroyed 33,000 e-mails so they could not be used against her as evidence in court. She conspired with Democratic National Committee officials Debbie Wasserman Schultz and Donna Brazile to steal the Democratic Party nomination from her primary opponent Social Democrat Bernie Sanders. And this is only what she did in the past eight years. If any man did even 10 percent of what she got away with over the past eight years (or even in the previous three decades), that man would have served time for the rest of his life.

Michelle Goldberg believes that female presidential candidates must only be selected from a list of smart, assertive, policy wonk women in the mold of Hillary Clinton, like Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, Minnesota Senator, Amy Klobuchar, and California Senator Kamala Harris. They must all be leftist United States Senators in the mold of Lucy van Pelt, with the same background as liberal lawyers. Their one magic solution to every problem is new legislation, administered by the federal government, and funded by heavy taxes on working families like mine. Republican women senators, like Iowa’s Joni Ernst, Nebraska’s Deb Fischer or West Virginia’s Shelley Capito, are not on Michelle Goldberg’s radar screen because they are not leftist enough for her taste.

Being a woman is not qualification enough to hold the highest public office. Not every American woman is worthy of being the President. Character matters. There are female murderers locked up in almost every state in the Union. There are female criminals everywhere. There are women in insane asylums in every city in America. There are women all over America who are not intellectually, emotionally or physically capable of serving. None of them should be the President for the same reason that I would not have them watch my children. Policies matter a lot. Every leftist idea under the sun, like free healthcare, free higher education, free jobs, free homes, free contraception, free food or free toilet paper, cannot be repackaged by the left as “women’s issues”. They must not be turned into laws, administered by Washington bureaucrats, and given away to women for free, with the costs put on a credit card to be paid by others.

I truly believe that there will be a woman President of the United States soon enough. Yet, for the sake of our country, I hope and pray that she is a Republican or Libertarian, not a liberal Lucy van Pelt like Hillary Clinton or the four senators championed by Michelle Goldberg. Give the American people a better female candidate, with great personal character and centrist-right policies, and they will be more than happy to vote for her.

Will We Ever Have a Woman As President

Hillary Clinton’s defeat galvanized Democratic women. But along with the trauma of her loss is the dread of repeating it.

Michelle Goldberg

Slate

May 31, 2017

On May 16, members of the Democratic Party elite gathered at a Four Seasons in Georgetown for the Center for American Progress’ Ideas Conference, which was widely seen as a cattle call for potential 2020 presidential candidates. If everyone hadn’t been so distracted by the unfolding Trump-Russia scandal, it might have felt more notable that among the speakers rumored to be 2020 prospects were four women: Sens. Elizabeth Warren, Kirsten Gillibrand, Kamala Harris, and Amy Klobuchar. The next Democratic primary may have not just one woman but a field of them. “The resistance is female, in every way,” CAP President Neera Tanden told me.

It would be thrilling to see several women step forward to challenge President Donald Trump. If they do, we might end up remembering Hillary Clinton as the Barry Goldwater of feminist presidential candidates: a figure whose epochal defeat inspired a triumphant next wave. For a woman to beat Trump—or Mike Pence, if Trump were forced from office—would help heal the psychic injuries of this dystopian period of macho kakistocracy. “We continue to underestimate the psychological wound of having a man become president after he said what he said about women on the Access Hollywood tape,” Tanden says. For a woman—maybe even a black woman, in the case of Harris—to take Trump down would be sweet revenge.

At the same time, for those who believe that sexism played a significant role in Clinton’s defeat, the thought of Democrats nominating another woman is a little bit terrifying. Last November, says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake, “We discovered how difficult it is to elect a woman to executive office.” Are we really ready to try again?

* * *

On May 2, when Clinton spoke about the role that sexism played in her defeat, many pundits reacted with contempt, disgusted that she was not accepting complete responsibility for being the worst candidate ever. “Hillary Clinton adds misogyny—and more—to the list of things she blames for her 2016 loss,” a sneering Washington Post headline said. While no one actually thinks sexism is the only reason Clinton lost, there’s an abundance of polling data suggesting that it at least contributed. According to a January PerryUndem study, a third of men who voted for Trump, as well as a quarter of women who voted for him, said that men generally make better political leaders than women. By 10 points, Republican men said they thought women are better off in America than men are.

Last February, as Clinton and Trump battled for their parties’ nominations, political science professor Dan Cassino and his colleagues at Fairleigh Dickinson University undertook a study about how fears of emasculation affected men’s political preferences. The researchers conducted a survey of 694 registered voters in New Jersey. Before being asked about the presidential candidates, half the respondents were reminded that, in a growing number of households, women earn more than men; the respondents were then asked if the same is true for them.

Asked about a matchup between Clinton and Trump, men who’d been queried about earning power were 8 percentage points less likely to support Clinton and 16 points more likely to support Trump, a total swing of 24 points. Support for Bernie Sanders versus Trump was unaffected by the question.

In a follow-up national study, Cassino and his colleagues tried to measure the effect of what they call “ambient gender role threat” on political preferences. This time, they primed respondents with a question about whether the media treats men too harshly; it led to a seven-point shift toward Trump among men. Cassino believes that Clinton, because of her long and controversial tenure in public life, is uniquely threatening to many men but that other female candidates could easily evoke similar masculine anxieties. “It’s very hard to be a woman running for office who doesn’t represent some sort of threat to men’s roles,” he says.

What’s more, the economic trends underlying male panic aren’t changing anytime soon. “The industries that are being hurt by automation are industries that are dominated by men,” Cassino says. Meanwhile, women are outstripping men in educational attainment. “That personal gender role threat is much more pronounced than it has been in the past. We’re seeing it affecting more men.”

In such an environment, Cassino believes that any woman running for president is at a disadvantage. “On the national stage, there is an increasing number of men who feel they’re being discriminated against,” he says. Such men are heavily prevalent in swing states such as Ohio and Michigan, former sites of the industrial jobs that used to offer middle-class wages to men without college degrees. “If you’re running for president and you’re a woman, you are running uphill,” he says.

It would be nice to believe that Elizabeth Warren could speak to some of these economically anxious men. Daughter of a janitor, the Massachusetts senator is a passionate economic populist; no one would accuse her of being too cozy with Wall Street. To Clinton’s liberal critics, Warren is Clinton’s opposite: steadfast where Clinton is prevaricating, authentic where Clinton is calculating. Unlike Clinton, Warren is not attached to a troublesome man whose reputation has at times overshadowed her own. She hasn’t spent decades in the public eye serving as a synecdoche for unseemly female ambition.

Yet Warren is not invulnerable to some of the attacks that undermined Clinton. In April, Warren appeared on Real Time With Bill Maher to promote her book, This Fight Is Our Fight: The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class. Maher asked her to explain why so many in the white working class prefer Trump to her: “They’re still with him. They’re not with you. Explain to me what that disconnection is.” When Warren started to push back, Maher added, “They don’t like you, Pocahontas,” using Trump’s derisive nickname for her. The moment recalled the countless times Clinton has been asked to account for people’s dislike of her, a question with no good answer.

It was hardly the first time Warren had been hit with the “unlikeable” charge. When she ran for Senate in 2012, she faced a stream of stories about how much more congenial people found her opponent, Scott Brown. “People admire Warren, who has a resume chock full of impressive accomplishments,” said one Washington Post piece. “They want to hang out—or have a beer—with Brown.” The website of Boston’s NPR station ran a piece about well-educated liberal women who were turned off by Warren: “Demographically she’s one of them, but politically she’s losing them. They say they won’t vote for Sen. Scott Brown, but Warren and her hectoring, know-it-all style leaves them deeply disappointed.”

A February Politico/Morning Consult poll found a generic Democrat easily beating Trump in 2020 but Trump beating Warren by six points. Politico interpreted this as a sign that Democrats could be in trouble “if they continue their lurch to the left.” But the finding could just as easily be an indication that a significant number of voters can’t stand to feel lectured by a wonkish older woman.

In politics, identifying misogyny risks reinforcing it. It can be hard to describe the dangers of running for office while female without instantiating those dangers; to speculate about what kind of slurs might be thrown at a candidate is to put those slurs out there in the first place. Feminists know this, yet layered on top of the trauma of Clinton’s loss is the dread of repeating it. “Although a lot of people are very enthusiastic about Elizabeth Warren, I think that were she to become a real contender, all of the responses to extremely competent, forceful women would start to work against her,” says feminist historian Susan Bordo, author of the recent book The Destruction of Hillary Clinton. “We’d be hearing, ‘She’s shrill. She’s schoolmarmish.’ ”

Sure enough, a recent McClatchy story describes the Republican plan to use pages from the anti-Clinton playbook against Warren in her 2018 Senate race; the long-range strategy is to inflict damage ahead of a possible presidential run. “We learned from our experience with Secretary Clinton that when you start earlier, the narratives have more time to sink in and resonate with the electorate,” a Republican operative said. If Democrats allow themselves to be pre-emptively spooked by possible Republican attacks, they may be falling into the right’s trap. All the same, we’ve seen such attacks work.

The double bind for female candidates is that women who contend for power are less likely than men to be seen as likeable, but likeability has outsized importance for them. The Democratic pollster Celinda Lake points to research showing that voters will support a qualified man they dislike but not an unlikeable, qualified woman. In 2016, she notes, 18 percent of the voters disliked both candidates, and these voters went for Trump by double digits.

* * *

Right now, we lack a template for a likeable female presidential candidate. Kirsten Gillibrand, a New York senator like Clinton before her, is widely considered to be more personable and charismatic than her predecessor, but she’s already been caricatured in similar ways. In her 2014 book Off the Sidelines—for which Clinton wrote the forward—Gillibrand describes how, upon entering the Senate, “opponents and detractors” nicknamed her “Tracy Flick,” after the perky, dementedly ambitious character from the movie Election. “It was a put-down to me and other ambitious women, meant to keep us in our place,” she writes. There’s no telling how much people will like Gillibrand after an overwhelming campaign of Republican demonization.

Or consider California Sen. Kamala Harris, who seems, at least on the surface, a potential distaff analogue to Barack Obama. (Indeed, the Washington Post once ran a piece headlined, “Is Kamala Harris the next Barack Obama?”) Like Obama in his Senate days, she’s a telegenic newcomer to the national stage with a melting-pot background (she is the daughter of immigrants from Jamaica and India). She’s garnered buzz for her early and consistent opposition to Trump, including her sharp questioning of John Kelly, now head of the Department of Homeland Security, over how he would handle undocumented immigrants who’d been brought to the U.S. as children. At 52, she’s relatively young, and for several decades Democrats have done best with young candidates: John F. Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Obama were all under 55 when they were elected.

But as the legal scholar Joan Williams once said, “Men are often judged on their potential, but women are judged on their achievements.” It’s far from clear that any woman could mimic Obama’s rocket trajectory, because women have to spend more time than men do proving themselves capable. Then once they’ve put in the time and paid their dues, they can easily be written off as too old. Hillary Clinton spent decades working to become overqualified for the presidency, culminating in 112 countries visited and nearly 1 million miles flown as secretary of state, and her efforts were rewarded with Trump and his supporters successfully questioning her “stamina” during the 2016 campaign.

Given the endless ranking of Clinton’s flaws as a candidate both during and after the election, it’s easy to forget that before entering the race, she was the most popular politician in the country; at one point, the Wall Street Journal reported her favorability rating as an “eye-popping” 69 percent. But people perceive women differently when they’re contending for executive office than when they’re running for a collaborative body, like the Senate, or serving below a powerful man. “All the ancient clichés about women—are they trustworthy, are they strong enough to be commander in chief—all those come into play,” says Madeleine Kunin, the former governor of Vermont. “If you’re too tough, you’re not feminine. If you’re too feminine, you’re not tough enough. There’s a very small space between those two that is safe territory.”

Clinton was never able to find that sweet spot. As she recently told New York magazine’s Rebecca Traister, “Once I moved from serving someone—a man, the president—to seeking that job on my own, I was once again vulnerable to the barrage of innuendo and negativity and attacks that come with the territory of a woman who is striving to go further.”

If you buy Clinton’s analysis of the challenges she faced—and I do—it’s hard to know what to do with it. It would be a very dark irony if a feminist reading of 2016 led to the conclusion that Democrats shouldn’t nominate a woman in 2020. According to Cassino, the long-term solution to male anxiety about female leadership “is that you run women so often that it becomes absolutely unremarkable.” Seen that way, the next primary could mark the beginning of this process. “It’s a coming of age,” Lake says. “It’s not just about a woman candidate. It’s that all the best candidates are women.”

The shock of 2016 has certainly brought women off the sidelines. EMILY’s List, an organization that works to elect pro-choice Democratic women, reports that more than 11,000 women reached out to it about running for office in the first four months of this year (compared with about 900 in all of 2016). Ezra Levin, one of the founders of the Tea Party–inspired anti-Trump Indivisible Movement, says that women lead most of the group’s chapters. “Remember, the Democratic Party is 59 percent female,” says Lake, who adds that while Democrats’ first priority is beating Trump, “there would be quite a bit excitement about having a woman.”

Still, it’s easy to imagine the furious female energy in the Democratic Party expressing itself as it has so often in the past: by lifting up a magnetic young man. French President Emmanuel Macron’s famously aggressive handshake has shown there’s power in going after Trump on his own masculine turf. An American politician who could similarly unman the president would create a lot of enthusiasm. Many American women want to break the male lock on the presidency, but they also want to save the republic, and it’s all too possible that those two goals are at odds. “Frankly, at this point, I don’t care if it’s a woman or a man,” Kunin says. “I’d like to live long enough to see a woman president, but I think we all feel we have to change regimes.”